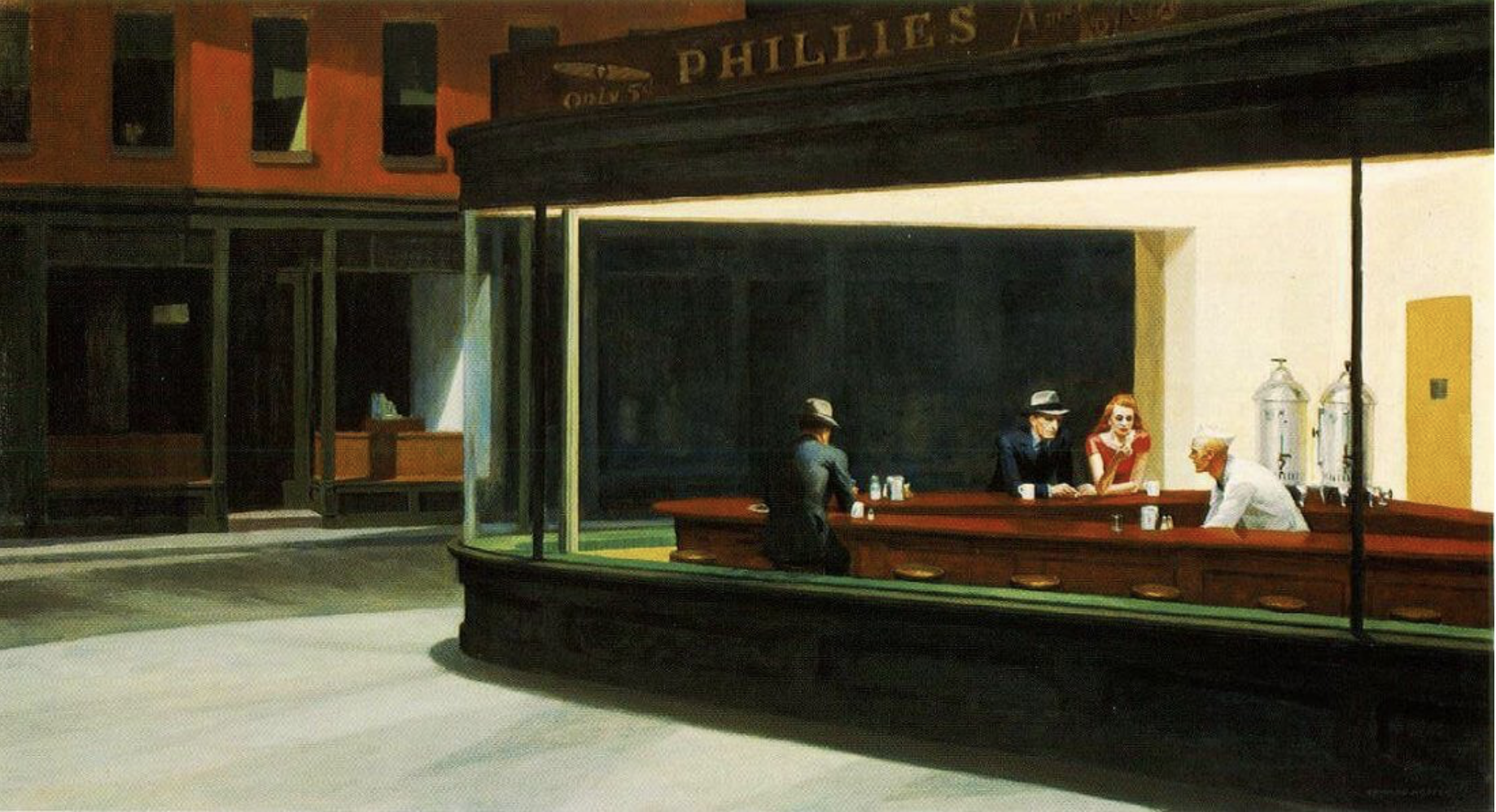

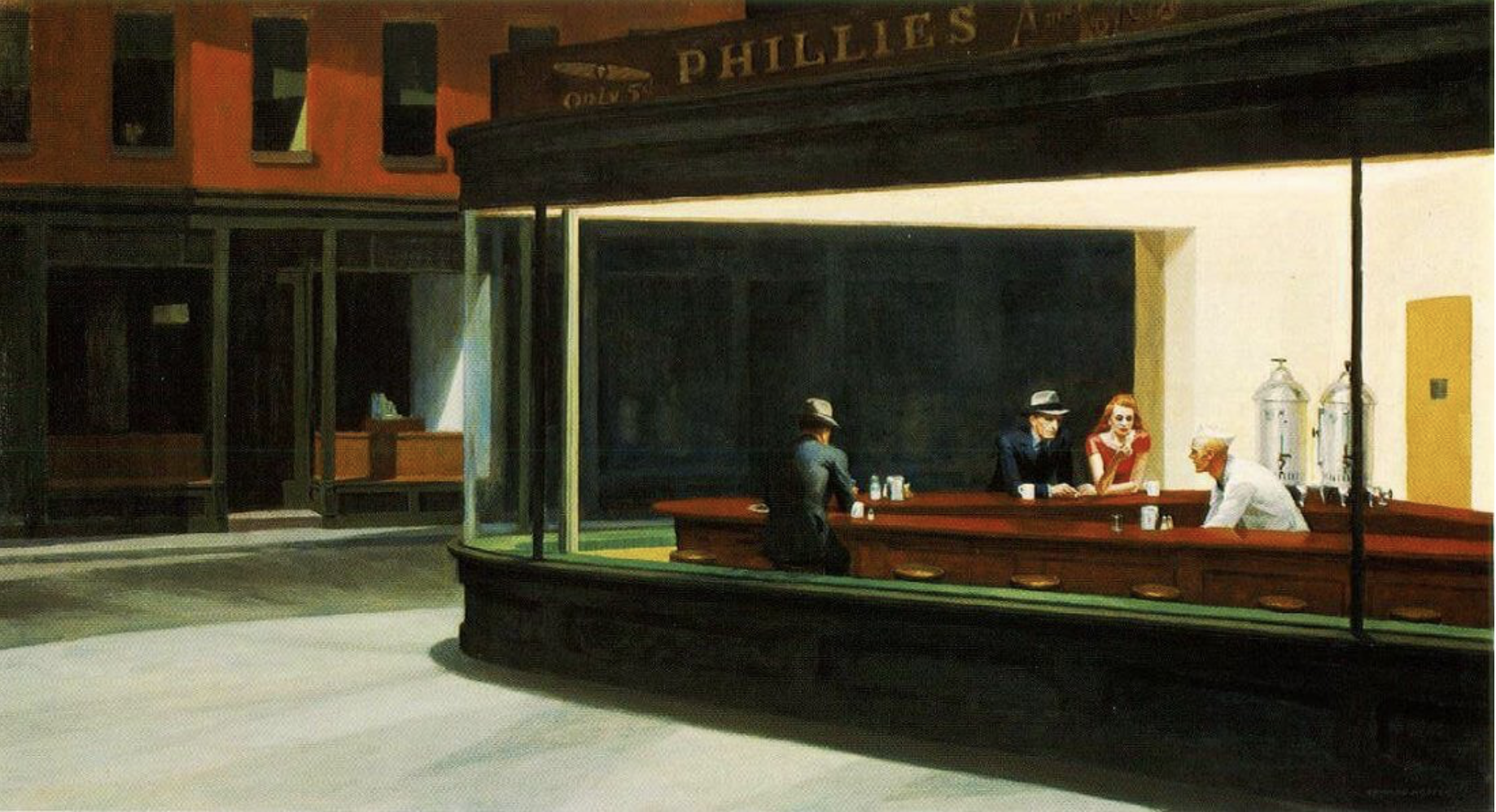

Nighthawks by Edward Hopper, 1942

Rose

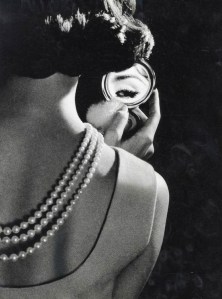

Rose looked at her reflection in the polished mahogany counter. She didn’t look good. The day had caught up to her, stripped her color and sharpened her face. She dabbed at her lipstick with a napkin. Too red. It looked funny. Rose put the napkin down. She used to like that red. So had Eddie. Eddie had liked that color.

Red, red lips for my red, red, Rose….

Rose’s hand plucked at her earring, her coffee, her locket, before inching over to rest on Rob’s sleeve. She liked the feel of his woolen jacket under her quick, nervous fingers. Nice and warm. Solid. Rob. She sighed. It had been a long day. It was time to go. She wanted to say that. It’s been a long day. It’s time to go. But his downcast eyes trapped the words in her mouth. He wasn’t ready yet. She could wait.

Widowed at thirty. Thirty was too young for how she felt. For how she looked too. Her reflection looked worn out and old—not pretty anymore. Her eyes slid to the floor. She didn’t really care. Everyone was dead. Eddie was dead. The baby was dead. Her father—hers and Rob’s—was dead, but that was nothing to cry about. Their father had been a lucky son-of-a-bitch.

Rose glanced at her brother and stopped the thought, just in case he read her mind. Sometimes he could. He couldn’t, not really. But sometimes he knew. She couldn’t read his either, but sometimes…. She clutched her thick, glazed coffee mug with both hands, prepared to wait.

It’s been a long day. It’s time to go home.

She looked at Robbie’s profile, his hawkish face, and quietly looked away.

The dead weren’t lucky, but she felt like they were. She couldn’t say that to anyone, especially her baby brother. He didn’t need to hear it. He’d done enough already – more than she wanted him to. He’d visited her in the hospital and tied pink ribbons around her wrists. He came by or called every day. He worried so much. She made him worry.

You worry, Robbie. You worry too much.

She was tired. It was time to go home.

Rose sighed, a small, shallow breath. Everything was done. This time he’d have nothing to find. Poor Robbie. She was glad they’d spent the whole day. Rose fingered her locket. The gold was warm. It felt soft when she pressed it. There was a picture of Eddie and the baby inside.

She glanced at her brother through her sweep of red hair. Red, red hair. Red, red Rose. Rob’s comfortable silence was the only thing she would miss. His face looked dark, like a shuttered house. No lights. Locked doors. She had to wait for him to be ready. They would sit together in this in-between place, coffee cold in their cups. When he was ready, he would take her home, and then she would go to Eddie and the baby. She loved her brother. She could wait.

Robert

Robert knew that she was going to try it again. He could read it like newsprint in the lines around her mouth. He missed her smile, her real smile, her cracking, half-cocked grin. He hadn’t seen it in months. Instead he got what she gave him now…pale lips under too much lipstick. Her hand was cold on his arm.

She’d gotten dressed up for their day out, special occasion dressed up—Hayworth hair, her favorite pink dress, she’d even worn perfume. But her bones were sharp beneath her collar. Her wrists were thin and hard. He wished she’d worn a sweater. It was turning cold, too cold for a thin, silk dress.

Why don’t you bring a sweater, Rosy?

I’ll be okay.

The second she’d said that, he’d known. That dress, her hair, her too bright face…he’d known exactly what was coming, and he didn’t want to know.

He lit a cigarette and let it burn. Tiny column of ash. Then he lit another. Beside him Rose shifted, patient, silent. She wanted to go home.

See you tomorrow, Rose

I love you, Rob.

Robert sipped his coffee. He should say something. He should stop her. But, Jesus, she looked spent up…. Rob glanced at his sister, though the sweep of her strawberry hair, but he couldn’t see her face. He wasn’t sure he wanted to. Robert signaled for the check. It was time to take her home.

“More coffee?”

Robert paused.

The waiter poured.

One more cup.

Charlie

Wish that kid would quit staring and do his job. Goddamn coffee’s cold.

Across the diner, the old man hunched over the counter like a bulldog over a bone. He eyed the yellow-haired waiter, who was eyeing the redheaded girl. Like staring was going help her. A gal like that never left her man, not if he beat her into the ground. After thirty years he knew.

Charlie rubbed his bum knee. He wished he could sleep. He hadn’t slept since he’d retired. Not a full eight hours. Not in a month. Best wishes, Charlie! Retirement—you lucky son-of-a-bitch!

Yeah. Real lucky.

Charlie leaned back on the hard stool, regretting the watch the boys at the precinct had given him. He hated fishing, hated crosswords. His buddies were still on the force. Doris was remarried and Katie was busy, making a life of her own. She’d even gotten a job—secretary at some firm. Smart girl. Katie had always been smart. Maybe not pretty, but smart. He could hear Doris telling her to dress up nice for work. Christ, he wished Doris would shut-up.

Charlie shot the waiter a look and clacked his cup softly. The kid strolled over, refilled it from the urn and handed it back to him. Up close, Charlie realized, the kid wasn’t much of a kid. Pushing thirty, he’d bet. Charlie grunted. At twenty-six, he’d already been on the force for five years. Guy should get a real job.

Charlie looked out the diner’s plate-glass window at the dark, disinterested street. What did you do when you got cut loose? Kid’s got his whole life and he wastes it, like it’s something to toss away. The old man shifted. He was starting to hate that kid….

He should probably head home. It was a long walk back to his place. Maybe that would wear him out. He reached for his wallet, straining the seams of his suit. Cheap suit. Work suit. He took out his Luckies instead. One cigarette. One more cup. Then he’d toss a buck on the counter and take the long walk home. Back to his apartment. He hated that apartment. He hated the way it looked—half empty, full of nothing worth saying, like old newsprint. He hadn’t seen it that way before. He hadn’t had time—he’d barely ever been home. Now he saw every night. Charlie sucked the hot coffee between his teeth.

Christ, he wished he could sleep.

Joe

That lady looks sick. Joe glanced up from a tray of half-empty saltshakers. What’s she doing out so late with that guy, anyway? She looks like she should be in a hospital or something….

Joe shook his head and refilled the shakers without taking his eyes off the lady in the pink dress. He was good at working and watching. He never spilled.

Look at how she’s holding his arm, he thought. Like she’s gonna drown and he’s the only thing keeping her afloat.

That was good, Joe thought. He had to write that down. He stopped pouring and wiped his hands before getting out the little notebook he kept in his apron pocket.

He loved working the late shift. Nothing like it for writer’s block. Nothing like it for inspiration. The lady and her fella were great. He had to use them somewhere…maybe he’d put her in a sanitarium and make the guy her lover. And the guy… a private eye with a shady past? Maybe he broke her out and now they’re on the run. However Joe wrote it, it was gonna be tragic. That lady was tragic all over.

Joe glanced across the counter at the old guy sitting on his own. Not much there. Just a sad sack. He wasn’t as compelling but Joe could work with it. Maybe a tired crime boss or a has-been reporter. Joe studied the man nursing his hundredth cup of coffee. Thickset. Stubborn build. Angry mug. Joe nodded and grinned. He’d make the old guy the redhead’s father. Iron fist with heart of gold.

The old guy shot Joe a belligerent look.

Skip the heart of gold.

Joe shrugged. Even after he’d sold the novel, he’d still work the graveyard shift. He loved the diner at night. Nothing like it for writer’s block. Nothing like it for inspiration.

Joe pulled out a pen. Down the counter, the man paid the tab and helped the lady up. She stumbled. He caught her. Joe bent over his notes. He barely looked up as they left.

THE END